Dwelling on the Korean Pavilion

Pai, Hyungmin

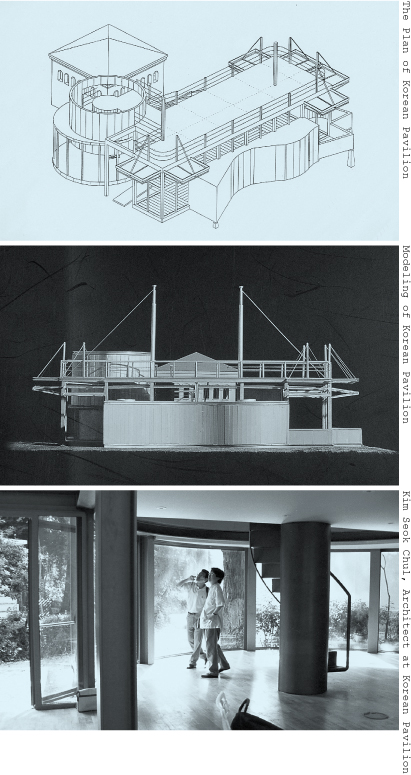

The Giardini is a kind of city. During the Biennale, it is a bustling garden city of small museums. Otherwise, during long periods of inactivity, it feels like a luscious necropolis of large mausoleums. In this strange city, there is a pavilion that eludes both of these designations. The Korean Pavilion is more like a house. Secluded behind the Russian, Japanese and German pavilions, undetected along the sub-axis of the Giardini, it has the scale and privacy of a house. From the exterior, the different elements - a pre-existing brick shed, a tiered cylinder, a light steel-framed entrance ? seem to designate the different functions of a house. It has a front garden, a back yard, and a roof terrace. We enter through a porch, into a spacious rectangular hall. It is a bright “living room” with a sky-light and ample glass walls that filter light through wooden screens. Fold up the wooden screens and hang them on to cantilevered canopies, as you would in a hanok (the traditional Korean house), and the living room opens up to the gardens and the waters of the San Marco Canal. There are even back porches that look out to the Canal. An undulating wood panel wall unexpectedly runs along one side of the hall; on the other side, a skylight slants down to a lower ceiling area. This is then the dining and kitchen area of the house, with doors that lead to the back of the house and the existing shed. The square brick shed, once used as an office and a toilet, seems almost private, like a bedroom chamber. A circular stair at the center of the cylinder once led up to an upper floor that still houses a toilet and storage space.

Rather than regular, neutral, white spaces, the architects Kim Seok Chul and Franco Mancuso have provided a differentiated space of diverse materials, shapes, and colors. They built one of the few pavilions in the Giardini in which painting was not the focus of its program. With its use of light materials assembled on site, with its many indentations, protrusions, additions, and curves, the pavilion has the feel of a modern vacation house. At the same time, like many of the pavilions in the Giardini, it is over-burdened with architectural metaphors and obligations to national identity. Alternatively a Korean house, a UFO, a sail boat anchored on to a Venetian canal, it boasts nautical posts and wires that pretend to be part of a tensile structure. In 2005, with Choi Jeong Hwa’s terrace installation, the cables were taken out and have not been reinstalled since. It is a house that wants to be too many things. Unable to decide what to forget, it dwells on too many things.

Notwithstanding this confusion, the question still begs, “Why a house?” In the West, art and its exhibition spaces are irrevocably intertwined in a particular historical trajectory. The picture gallery, the white cube, warehouses, and urban spaces; each type of space evolved with fundamental shifts in the nature of art. This trajectory, though very relevant to Korea, does not apply. With its short, disjointed history of painting, I would argue that “modernist painting” never existed in Korea. If so, then there is also no white cube to speak of. In the obligatory search for a “Korean” space for exhibition and performance, one must recall the munbang, the private study where the Confucian literati engaged in calligraphy and painting, and the madang, the outdoor spaces of multiple performances. Though the Korean architect Kim Seok Chul is better known for his aggressive, sculptural forms, in his engagement with the Korean house, he has produced an accommodating space. It is a space that allows itself to be adapted and changed, all within the scale of the house. It is a kind of hospitality that distinguishes it from most of the heavy monuments in the Giardini. We may contrast it, for example, with the German Pavilion next door, whose history and forms have provoked strong responses. We will certainly not forget Hans Haacke’s entry as a self-made vandal, smashing the marble floors furbished under the direction of Hitler.

In the short life of the Korean Pavilion, its exhibitions have reacted to the building and transformed it in different ways. Because of the sheer scale and locality of the pavilion, the Korean exhibitions have absorbed and performed this peculiar domestic scene. Most recently, it housed Lee Yongbaek’s mannequin scenes of violence and lamentation, inevitably read as domestic. In 2010, Cho Jung Goo fit a hanok into the interior of the pavilion. In 2005, Choi’s walls of red plastic baskets made a comfortable addition to the house. With the household utensils and bedroom mirrors installed by the artists, the architecture of the Korean pavilion raises the basic question of what it means to be at home and what it means to be away. Being at home is an elemental yet vulnerable condition. As the last pavilion in the Giardini, its very place, both spatially and temporally, evokes this vulnerability. From the view point of the Giardini axis, one could take it away, and it would seem that nothing had changed. If the Western aesthetic is about selective forgetfulness, home is one of the things most often forgotten. Western culture often acts as if it has no home. But architecture cannot totally forget the house and the life of the home. As Adolf Loos argued a century ago, this is perhaps where architecture operates, along the different boundaries between art and the everyday. The architecture of the pavilion, like all the other national pavilions in the Giardini, sets up a particular datum in relation to the changing exhibitions and discourses that co-habit the spaces. The question it raises is as much about power, of the connections between the strong and the weak, as it is of what is acknowledged and what is forgotten. Hence the belated immersion of this house in this strange garden of museums, in a city with traditions polar opposite to those of an older Korea, enables a productive engagement between different mechanisms of memory. Between wanting to be at home and wishing to be somewhere else, the Korean Pavilion is a frustrating yet open space, a space that continues to dwell on what it wants to be.

*This text was commissioned as a part of the project by Diener & Diener Architects during the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012

-

HYUNGMIN PAI

He is Professor, Architecture, University of Seoul and co-editor/principal author of The Key Concepts of Korean Architecture (2012). He was curator for the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2008); editorial curator for the Kim Swoo Geun exhibition “Dense Modernities” (Berlin Aedes Gallery, 2011); and head curator for the 4th Gwangju Design Biennale (2011).

Pai, Hyungmin

The Giardini is a kind of city. During the Biennale, it is a bustling garden city of small museums. Otherwise, during long periods of inactivity, it feels like a luscious necropolis of large mausoleums. In this strange city, there is a pavilion that eludes both of these designations. The Korean Pavilion is more like a house. Secluded behind the Russian, Japanese and German pavilions, undetected along the sub-axis of the Giardini, it has the scale and privacy of a house. From the exterior, the different elements - a pre-existing brick shed, a tiered cylinder, a light steel-framed entrance ? seem to designate the different functions of a house. It has a front garden, a back yard, and a roof terrace. We enter through a porch, into a spacious rectangular hall. It is a bright “living room” with a sky-light and ample glass walls that filter light through wooden screens. Fold up the wooden screens and hang them on to cantilevered canopies, as you would in a hanok (the traditional Korean house), and the living room opens up to the gardens and the waters of the San Marco Canal. There are even back porches that look out to the Canal. An undulating wood panel wall unexpectedly runs along one side of the hall; on the other side, a skylight slants down to a lower ceiling area. This is then the dining and kitchen area of the house, with doors that lead to the back of the house and the existing shed. The square brick shed, once used as an office and a toilet, seems almost private, like a bedroom chamber. A circular stair at the center of the cylinder once led up to an upper floor that still houses a toilet and storage space.

Rather than regular, neutral, white spaces, the architects Kim Seok Chul and Franco Mancuso have provided a differentiated space of diverse materials, shapes, and colors. They built one of the few pavilions in the Giardini in which painting was not the focus of its program. With its use of light materials assembled on site, with its many indentations, protrusions, additions, and curves, the pavilion has the feel of a modern vacation house. At the same time, like many of the pavilions in the Giardini, it is over-burdened with architectural metaphors and obligations to national identity. Alternatively a Korean house, a UFO, a sail boat anchored on to a Venetian canal, it boasts nautical posts and wires that pretend to be part of a tensile structure. In 2005, with Choi Jeong Hwa’s terrace installation, the cables were taken out and have not been reinstalled since. It is a house that wants to be too many things. Unable to decide what to forget, it dwells on too many things.

Notwithstanding this confusion, the question still begs, “Why a house?” In the West, art and its exhibition spaces are irrevocably intertwined in a particular historical trajectory. The picture gallery, the white cube, warehouses, and urban spaces; each type of space evolved with fundamental shifts in the nature of art. This trajectory, though very relevant to Korea, does not apply. With its short, disjointed history of painting, I would argue that “modernist painting” never existed in Korea. If so, then there is also no white cube to speak of. In the obligatory search for a “Korean” space for exhibition and performance, one must recall the munbang, the private study where the Confucian literati engaged in calligraphy and painting, and the madang, the outdoor spaces of multiple performances. Though the Korean architect Kim Seok Chul is better known for his aggressive, sculptural forms, in his engagement with the Korean house, he has produced an accommodating space. It is a space that allows itself to be adapted and changed, all within the scale of the house. It is a kind of hospitality that distinguishes it from most of the heavy monuments in the Giardini. We may contrast it, for example, with the German Pavilion next door, whose history and forms have provoked strong responses. We will certainly not forget Hans Haacke’s entry as a self-made vandal, smashing the marble floors furbished under the direction of Hitler.

In the short life of the Korean Pavilion, its exhibitions have reacted to the building and transformed it in different ways. Because of the sheer scale and locality of the pavilion, the Korean exhibitions have absorbed and performed this peculiar domestic scene. Most recently, it housed Lee Yongbaek’s mannequin scenes of violence and lamentation, inevitably read as domestic. In 2010, Cho Jung Goo fit a hanok into the interior of the pavilion. In 2005, Choi’s walls of red plastic baskets made a comfortable addition to the house. With the household utensils and bedroom mirrors installed by the artists, the architecture of the Korean pavilion raises the basic question of what it means to be at home and what it means to be away. Being at home is an elemental yet vulnerable condition. As the last pavilion in the Giardini, its very place, both spatially and temporally, evokes this vulnerability. From the view point of the Giardini axis, one could take it away, and it would seem that nothing had changed. If the Western aesthetic is about selective forgetfulness, home is one of the things most often forgotten. Western culture often acts as if it has no home. But architecture cannot totally forget the house and the life of the home. As Adolf Loos argued a century ago, this is perhaps where architecture operates, along the different boundaries between art and the everyday. The architecture of the pavilion, like all the other national pavilions in the Giardini, sets up a particular datum in relation to the changing exhibitions and discourses that co-habit the spaces. The question it raises is as much about power, of the connections between the strong and the weak, as it is of what is acknowledged and what is forgotten. Hence the belated immersion of this house in this strange garden of museums, in a city with traditions polar opposite to those of an older Korea, enables a productive engagement between different mechanisms of memory. Between wanting to be at home and wishing to be somewhere else, the Korean Pavilion is a frustrating yet open space, a space that continues to dwell on what it wants to be.

*This text was commissioned as a part of the project by Diener & Diener Architects during the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012

-

HYUNGMIN PAI

He is Professor, Architecture, University of Seoul and co-editor/principal author of The Key Concepts of Korean Architecture (2012). He was curator for the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2008); editorial curator for the Kim Swoo Geun exhibition “Dense Modernities” (Berlin Aedes Gallery, 2011); and head curator for the 4th Gwangju Design Biennale (2011).

한국관에 머물다

배형민

쟈르디니는 일종의 도시다. 바쁜 전시 기간 중에는 작은 박물관들로 채워진 전원도시다. 하지만 전시가 없는 긴 시간 동안은 숲 속에 커다란 추모관들이 늘어선 네크로폴리스와 같은 곳이다. 이 이상한 도시에 박물관도 추모관도 아닌 전시관이 있다. 한국관은 집이다. 스케일이 집과 같고, 집이 가져야 할 프라이버시도 있다. 러시아, 일본, 독일관 뒤에 숨어, 쟈르디니 축선에서 눈에 띄지 않는 곳에 자리잡고 있다. 기존의 벽돌 집, 계단식 원통 공간, 가벼운 철제 프레임의 입구 등, 밖에서 볼 때 다양한 집의 기능을 담고 있는 것 처럼 보인다. 이 집에는 앞 마당과 후정이 있고 옥상 테라스도 있다. 현관을 통해 여유로운 직사각형의 전시홀에 들어선다. 여기는 밝은 “거실”이다. 천창을 통해 빛이 내려오고 나무 스크린이 달린 넓은 유리창을 통해 빛이 스며들어온다. 한옥처럼 나무 스크린을 접어 켄틸레버 차양에 매달면 거실은 정원과 산마르코 운하로 열린다. 전시 홀의 끝에 산마르코의 물을 바라볼 수 있는 베란다가 마련되어 있다. 한쪽 벽은 나무 판넬이 물결치고 있고, 반대 쪽은 경사진 천창을 따라 천장이 낮은 원통 공간으로 이어진다. 이 공간이 식당과 부엌 같은 곳이다. 뒷문이 있고 벽돌 집으로 들어가는 입구도 여기다. 비엔날레 사무실과 화장실로 사용했었던 벽돌 집은 침실 처럼 숨어있는 느낌이다. 한 때 원통 공간 한 가운데에 2층으로 올라가는 원형 계단이 있었다. 원통 2층에는 지금도 화장실과 창고 공간이 있다.

김석철과 프랑코 만쿠소는 규칙적이고 중성적인 백색의 공간을 만들기 보다 색채, 형태, 재료가 다양한 공간을 만들었다. 회화를 위해 만들어졌던 대부분의 국가관과는 전혀 다른 공간을 만들어낸 것이다. 현장에서 조립한 재료들이 꺾어지고, 휘어지고, 덧 붙여져 있다. 마치 주말 주택 같은 가벼운 모습이다. 그러면서도 쟈르디니의 많은 전시관과 마찬가지로 수사학의 과잉과 국가 정체성의 무거운 부담을 안고 있다. 한옥이다, 비행접시다, 베니스에 정박한 돛단배다. 이 집은 이렇게 여러가지 이름으로 불린 적이 있다. 옥상에 돛대와 케이블을 달아 마치 인장 구조인 것 처럼 보이려 했다. 2005년 최정화의 옥상 설치로 케이블을 떼낸 후에 다시 매달지 않았다. 한국관은 너무 많은 것이기를 원한다. 너무 많은 것을 붙잡고 무엇을 놓아야할지 모른다.

이런 혼란 속에서, “왜 집인가?”라는 질문은 여전히 남아있다. 서구에서 예술과 그 전시 공간은 특정한 역사적 괘도 속에 함께 엮여 있다. 예술의 속성이 바뀌면서 그 전시 현장이 겔러리, 와이트 큐브, 창고, 도시 공간으로 변모해 나갔다. 이러한 역사적 괘도는 한국의 상황에도 의미는 있겠지만, 똑같이 적용될 수는 없다. 한국의 짧고 엇갈린 서양화의 역사 속에서 “모더니즘 회화” 자체가 존재하지 않았다면 와이트 큐브라는 개념 역시 없다. “한국적인” 전시와 퍼포먼스 공간을 만든다는 책무를 다하려면 사대부가 서예와 그림을 즐겼던 문방 공간이나 다양한 퍼포먼스를 수용했던 바깥 마당을 불러와야 한다.

김석철은 강한 조각적인 건축으로 알려져 있지만 한국적인 집을 만들려는 과정에서 포용력이 있는 공간을 만들었다. 집의 스케일을 유지하면서 전시에 따라 유연하게 변하는 건축을 창출하였다. 인접한 독일관에서는 한스 하케가 히틀러의 지시로 깔렸던 대리석 바닥을 부숴버린 적이 있었다. 무거운 반응을 불러일으키는 무거운 건축과는 달리 한국관에는 편안함이 있다. 짧은 역사 속에서도 한국관의 전시들은 그 건축에 다양하게 대응하고 이를 편하게 변형하였다. 한국관의 스케일과 현장감에 기대어 집의 풍경을 흡수하고 재연하였다. 가장 최근에 이용백 작가의 마네킨들은 가정이라 할 수 밖에 없는 폭력과 슬픔의 장면들을 담아냈다. 2010년에 건축가 조정구는 한국관 안에 한옥을 맞추어 넣었다. 2005년 최정화는 빨간 바구니 벽으로 2층을 편하게 증축했다. 작가들이 설치한 살림 집기와 함께 한국관의 건축은 집에 있다는 것과 집을 떠났다는 것이 무엇인지를 물었다. 집에 머문다는 것은 본질적이면서 불안한 상황이다. 독립된 국가관으로 쟈르디니에 마지막으로 자리 잡은 한국관은 공간적으로나 시간적으로 이런 위태로움을 말해준다. 쟈르디니의 축선에서 볼 때, 이 집이 없어진다해도 아무 것도 변하지 않았다고 생각할 수 있다. 선택적으로 기억을 지우는 것이 서양 미학의 핵심이라면, 가장 먼저 잊어버리는 것이 자기 집이다. 서양 문화는 마치 자기 집이 없는 것처럼 움직이곤 한다. 하지만 건축은 집과 집의 삶을 완전히 잊어버릴 수는 없다. 100년 전 아돌프 로스가 주장했던 것처럼 건축은 예술과 일상의 경계에서 작동하기 때문이다. 쟈르디니의 여러 국가관과 마찬가지로 한국관의 건축은 그 공간과 공생하는 전시와 담론의 규준선을 제공한다. 한국관이 던지는 질문은 권력의 문제, 즉 강한자와 약한자의 문제 뿐만 아니라 무엇을 기억하고 무엇을 잊을 것이냐는 문제를 제기한다. 미니 박물관들로 가득한 이상한 정원, 옛 한국과는 전혀 다른 수상 도시에 뒤늦게 자리잡은 이 집은 이질적인 기억 장치 간의 만남을 주선한다. 집에 머물고 싶은 마음과 집을 떠나고 싶은 욕망 사이에서 흔들리며, 한국관은 계속 자신을 찾아가는 열린 공간이다.

*이 글은 2012 베니스 비엔날레 건축전 기간 동안 건축가 프로젝트 <Diener & Diener>의 일환으로 쓰여진 것으로, 필자의 동의 아래 재수록되었다.

-

배형민

서울시립대 건축학과 교수, <The Key Concepts of Korean Architecture>(2012)의 공동 편집자 겸 저자. 그는 2008 베니스 비엔날레 건축전의 큐레이터, 김수근의 전시 <Dense Modernities>(Berlin Aedes Gallery, 2011)의 큐레이터, 2011 광주 디자인비엔날레의 수석 큐레이터를 역임한 바 있다.

배형민

쟈르디니는 일종의 도시다. 바쁜 전시 기간 중에는 작은 박물관들로 채워진 전원도시다. 하지만 전시가 없는 긴 시간 동안은 숲 속에 커다란 추모관들이 늘어선 네크로폴리스와 같은 곳이다. 이 이상한 도시에 박물관도 추모관도 아닌 전시관이 있다. 한국관은 집이다. 스케일이 집과 같고, 집이 가져야 할 프라이버시도 있다. 러시아, 일본, 독일관 뒤에 숨어, 쟈르디니 축선에서 눈에 띄지 않는 곳에 자리잡고 있다. 기존의 벽돌 집, 계단식 원통 공간, 가벼운 철제 프레임의 입구 등, 밖에서 볼 때 다양한 집의 기능을 담고 있는 것 처럼 보인다. 이 집에는 앞 마당과 후정이 있고 옥상 테라스도 있다. 현관을 통해 여유로운 직사각형의 전시홀에 들어선다. 여기는 밝은 “거실”이다. 천창을 통해 빛이 내려오고 나무 스크린이 달린 넓은 유리창을 통해 빛이 스며들어온다. 한옥처럼 나무 스크린을 접어 켄틸레버 차양에 매달면 거실은 정원과 산마르코 운하로 열린다. 전시 홀의 끝에 산마르코의 물을 바라볼 수 있는 베란다가 마련되어 있다. 한쪽 벽은 나무 판넬이 물결치고 있고, 반대 쪽은 경사진 천창을 따라 천장이 낮은 원통 공간으로 이어진다. 이 공간이 식당과 부엌 같은 곳이다. 뒷문이 있고 벽돌 집으로 들어가는 입구도 여기다. 비엔날레 사무실과 화장실로 사용했었던 벽돌 집은 침실 처럼 숨어있는 느낌이다. 한 때 원통 공간 한 가운데에 2층으로 올라가는 원형 계단이 있었다. 원통 2층에는 지금도 화장실과 창고 공간이 있다.

김석철과 프랑코 만쿠소는 규칙적이고 중성적인 백색의 공간을 만들기 보다 색채, 형태, 재료가 다양한 공간을 만들었다. 회화를 위해 만들어졌던 대부분의 국가관과는 전혀 다른 공간을 만들어낸 것이다. 현장에서 조립한 재료들이 꺾어지고, 휘어지고, 덧 붙여져 있다. 마치 주말 주택 같은 가벼운 모습이다. 그러면서도 쟈르디니의 많은 전시관과 마찬가지로 수사학의 과잉과 국가 정체성의 무거운 부담을 안고 있다. 한옥이다, 비행접시다, 베니스에 정박한 돛단배다. 이 집은 이렇게 여러가지 이름으로 불린 적이 있다. 옥상에 돛대와 케이블을 달아 마치 인장 구조인 것 처럼 보이려 했다. 2005년 최정화의 옥상 설치로 케이블을 떼낸 후에 다시 매달지 않았다. 한국관은 너무 많은 것이기를 원한다. 너무 많은 것을 붙잡고 무엇을 놓아야할지 모른다.

이런 혼란 속에서, “왜 집인가?”라는 질문은 여전히 남아있다. 서구에서 예술과 그 전시 공간은 특정한 역사적 괘도 속에 함께 엮여 있다. 예술의 속성이 바뀌면서 그 전시 현장이 겔러리, 와이트 큐브, 창고, 도시 공간으로 변모해 나갔다. 이러한 역사적 괘도는 한국의 상황에도 의미는 있겠지만, 똑같이 적용될 수는 없다. 한국의 짧고 엇갈린 서양화의 역사 속에서 “모더니즘 회화” 자체가 존재하지 않았다면 와이트 큐브라는 개념 역시 없다. “한국적인” 전시와 퍼포먼스 공간을 만든다는 책무를 다하려면 사대부가 서예와 그림을 즐겼던 문방 공간이나 다양한 퍼포먼스를 수용했던 바깥 마당을 불러와야 한다.

김석철은 강한 조각적인 건축으로 알려져 있지만 한국적인 집을 만들려는 과정에서 포용력이 있는 공간을 만들었다. 집의 스케일을 유지하면서 전시에 따라 유연하게 변하는 건축을 창출하였다. 인접한 독일관에서는 한스 하케가 히틀러의 지시로 깔렸던 대리석 바닥을 부숴버린 적이 있었다. 무거운 반응을 불러일으키는 무거운 건축과는 달리 한국관에는 편안함이 있다. 짧은 역사 속에서도 한국관의 전시들은 그 건축에 다양하게 대응하고 이를 편하게 변형하였다. 한국관의 스케일과 현장감에 기대어 집의 풍경을 흡수하고 재연하였다. 가장 최근에 이용백 작가의 마네킨들은 가정이라 할 수 밖에 없는 폭력과 슬픔의 장면들을 담아냈다. 2010년에 건축가 조정구는 한국관 안에 한옥을 맞추어 넣었다. 2005년 최정화는 빨간 바구니 벽으로 2층을 편하게 증축했다. 작가들이 설치한 살림 집기와 함께 한국관의 건축은 집에 있다는 것과 집을 떠났다는 것이 무엇인지를 물었다. 집에 머문다는 것은 본질적이면서 불안한 상황이다. 독립된 국가관으로 쟈르디니에 마지막으로 자리 잡은 한국관은 공간적으로나 시간적으로 이런 위태로움을 말해준다. 쟈르디니의 축선에서 볼 때, 이 집이 없어진다해도 아무 것도 변하지 않았다고 생각할 수 있다. 선택적으로 기억을 지우는 것이 서양 미학의 핵심이라면, 가장 먼저 잊어버리는 것이 자기 집이다. 서양 문화는 마치 자기 집이 없는 것처럼 움직이곤 한다. 하지만 건축은 집과 집의 삶을 완전히 잊어버릴 수는 없다. 100년 전 아돌프 로스가 주장했던 것처럼 건축은 예술과 일상의 경계에서 작동하기 때문이다. 쟈르디니의 여러 국가관과 마찬가지로 한국관의 건축은 그 공간과 공생하는 전시와 담론의 규준선을 제공한다. 한국관이 던지는 질문은 권력의 문제, 즉 강한자와 약한자의 문제 뿐만 아니라 무엇을 기억하고 무엇을 잊을 것이냐는 문제를 제기한다. 미니 박물관들로 가득한 이상한 정원, 옛 한국과는 전혀 다른 수상 도시에 뒤늦게 자리잡은 이 집은 이질적인 기억 장치 간의 만남을 주선한다. 집에 머물고 싶은 마음과 집을 떠나고 싶은 욕망 사이에서 흔들리며, 한국관은 계속 자신을 찾아가는 열린 공간이다.

*이 글은 2012 베니스 비엔날레 건축전 기간 동안 건축가 프로젝트 <Diener & Diener>의 일환으로 쓰여진 것으로, 필자의 동의 아래 재수록되었다.

-

배형민

서울시립대 건축학과 교수, <The Key Concepts of Korean Architecture>(2012)의 공동 편집자 겸 저자. 그는 2008 베니스 비엔날레 건축전의 큐레이터, 김수근의 전시 <Dense Modernities>(Berlin Aedes Gallery, 2011)의 큐레이터, 2011 광주 디자인비엔날레의 수석 큐레이터를 역임한 바 있다.