Migrating Futures

Ansan City + Gyeonggi Province / Republic of Korea (South Korea)

Provoking the possibilities of transcultural and lateral coexistence beyond existing national and political borders, N H D M investigates the spatiotemporal landscapes of foreign migrants in South Korea.

Seemingly peripatetic subjects, they have carved out spaces of self-determination and defined new notions of belonging with extreme specificity. N H D M provides six drawings depicting diverse past, present, and future geographies of intersecting timelines and identities in the landscapes of migrating futures, accompanied by selected responses to N H D M’s questionnaires discussing notions of home and belonging provided by individuals from migrants and immigrant communities.

Three drawings by N H D M presented together describe what constitutes the spaces of precarious domesticities lived by many transnational laborers and new immigrants.

Installation view:

The Korean Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia

Photo : Daniele Nalesso. Courtesy of the Korean Pavilion.

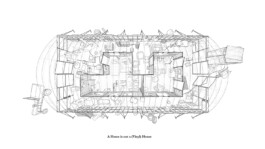

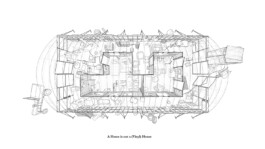

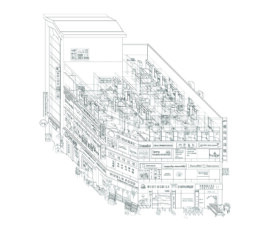

Domiciles Drawings

Three composite drawings, A Home is Not a Vinyl House (Domicile #1), World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2), and A Machine for Living In (Domicile #3) describe three most prevalent informal living situations currently experienced by many migrant workers in Korea, respectively describing a PVC vinyl house where seasonal agricultural workers are often housed, a Goshiwon (rentable study rooms) in urban setting usually serving as an initial housing solution for the newly arrived, and shipping container dormitories in small manufacturing sites in rural areas.

Home is not a (Vinyl) House

N H D M Architects, "Home is not a (Vinyl) House" from "Migrating Futures," 2023. Digital print on paper. © N H D M Architects, Courtesy of N H D M Architects.

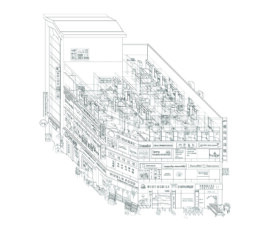

World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2)

N H D M Architects, "World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2)" from "Migrating Futures," 2023. Digital print on paper. © N H D M Architects, Courtesy of N H D M Architects.

Home is

The first series of Migrating Futures Survey Project "Home is" engages members of diverse migrant and immigrant communities residing in Gyeonggi Province to document their evolving notions of home as well as the realities of their dwelling. Materials presented here are selected from survey answers, interviews, photographs, drawings, poems, letters, and essays, collected from more than twenty-four immigrant and migrant organizations and eighty individuals, responding to prompts to reflect on the meanings of home, belonging, and future.

Six Scenes from Migrating Futures

Inspired by the artistic traditions of various Asian origins where landscape imageries often frame the critical environment that co-constitutes one's physical and/or ideological journey, and impelled by their layered construction that is both the re-presentation of the existing and the framework for the alternative world-making, the drawings in the hexaptych formation describe six anthropocenic landscapes of migration of multivalent timelines and identities, to seek the spaces of empathy and the possibilities of new comunality.

Ansan Series—Measure Island (Ansan #1), Take the 4 Train (Ansan #2), Banwol Archipelago (Ansan #3)--- depicts the past, present, and future geographies of migrancy set around the eponymous industrial town, often referred to as "Foreigners' City" or "Migrants' Town" by Korean nationals.

Three interwoven drawings—A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House), Head of Two Waters, and Masuk Moru—explore three sites of transnational migrant work most prevalent in Korea, respectively engaging the space of domestic care labor, small-scale factory production, and agriculture.

Measure Island (Ansan #1)

(Bottom Left)

The small island at the foot of Ansan has been called Measure Island for many generations as the local fishermen noted the changes in ebb and flow against its complete and round shoreline. The construction of the seawall in 1985 that allowed Korea's very first National Industrial Complex, Banwol, to flourish however not only mined away the sacred peak of the island but gradually turned it into a part of the new ground deprived of its livelihood. The drawing imagines a not-so-distant future when most of the built-up land is underwater and the Island is surrounded by the sea again. The man-made topologies of water and land on the island bring forward the parallel past and the present of migration. An elderly fisherman who fled North Korea is forced to flee his home again. A Korean migrant worker is put to the arduous labor of the "reclamation" of a foreign land in the 1980s Middle East.

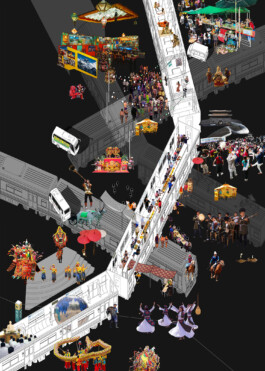

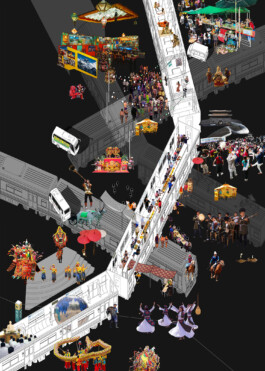

Take the 4 Train (Ansan #2)

(Top Center)

Prompted by the concentration of migrant workers in the 90s, the streets of Ansan's Wongokdong, or “Wongok Multicultural Special Zone” as the government puts it, grew to be a home away from home for many. The foreign migrant population in Korea increases steadily as the Ministry of Employment and Labor systematically recruits through the "Memorandum of Understanding" signed with sixteen countries while many are undocumented. The 4 train connecting Ansan to the center of Seoul has become a collective route of weekly rituals to visit the ethnic restaurants and places of worship, and occupy public spaces for cultural expressions and political actions. The spontaneous enclaves of diasporic hybrid culture and places of intersectional care and support have developed along the line, and in an imagined future, the train and its surrounding areas become an unbounded extraterritory where borders are eroded and all cultures are celebrated beyond the constriction of a "special zone."

Banwol Archipelago (Ansan #3)

(Bottom Right)

Ansan has been a space of coexisting yet divergent utopias, a testing ground for different idealisms. The ambitious terraforming of the Banwol Industrial Complex in 1977 was accompanied by the very first “New Town” in Korea, erected in the familiar blueprints of Howard's Garden City and Wright's prairie homes to welcome newcomers while displacing the existing population. The same footprint now holds ever-growing apartment towers that promise secure investments and pleasant living for native Koreans, while the factory jobs that Koreans avoid become a tentative basis for the “Korean dream.” In Banwol Archipelago, the City of Ansan is partially submerged creating a network of islands in the site of Banwol Industrial Complex that becomes a new aqueous collective ground for human and more than human migrating communities. The underwater factories become a refuge for a growing number of flora and fauna, and the toxicity of its industrial past becomes a foundation for a new habitat.

A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House)

(Top Left)

An ultimate instrument of personal financial safety inherited wealth and poverty, and a monument to the corporate capital accumulation aided by governmental policies, the overbuilt residential highrises cover the Korean cities and countryside, occupying much of the buildable land. A-PA-Tu complexes and their destruction and construction form cyclical and ubiquitous man-made geologies that replicate the preconceived ideas of the idealized nuclear family life. Unseen are the realities of domestic labor and care work performed more and more by foreign women in the global care chain within what some call “an international division of reproductive labor.” Intimate labor is much less shaped by intimacy than by the formidable structural forces of patriarchy, capitalism, and often racial disparity. A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House) describes the scene of vacant and "unkept" A-Pa-Tu buildings of the near future most likely from the continued market speculation, or, due to the end of the prescribed reproductive sphere. The empty towers become an opportunity for new inhabitants and new environments, or finally homes for their keepers.

Masuk Moru

(Bottom Center)

On the one hand, Masuk, a well-known furniture factory town, represents the quintessential rural industrial town in Korea, where population decline closes schools and the plans for large-scale development threaten the fabric of its small-town life. On the other hand, Masuk is a place of rare intersectional communality where the inhabitants and carers of the long-historied Leper colony embrace the migrant workers as part of their own community, offering a sanctuary from labor abuse and other difficulties of migrant life. Masuk Moru depicts a future scene of an abandoned elementary school, where the ideologies of nation-state used to be foregrounded for the next generations. Now taken care of and inhabited by transnational inhabitants, who are able to negotiate the new environments with the old, the mobility with the stability, the school becomes a space of new types of knowledge production and exchange where different notions of work and belonging shape the new starting point.

Head of Two Water

(Top Right)

Located at the scenic convergence of two water bodies (one from North Korea and one downstream from Seoul), Head of Two Water was once a much smaller river that expanded to its present size when a dam was constructed in 1972 to supply clean water to Seoul, inundating and displacing small farming communities and with great ecological implications. In the Tonle Sap area in Cambodia home to many of this region's seasonal agricultural workers, climate change threatens their livelihood in an opposite way by not inundating and depleting the nutrition in the soil, prompting more people to submit to the remittance economy. Foreshadowing an impending drop in water levels due to climate change, Head of Two Water imagines a future where the waters return again to their historic extents producing new land and a new relationship between land and who cultivate it.

Take the 4 Train

N H D M Architects, "Take the 4 Train" from "Migrating Futures," 2023. Digital print on paper. © N H D M Architects, Courtesy of N H D M Architects.

Migrating Futures

Ansan City + Gyeonggi Province / Republic of Korea (South Korea)

Provoking the possibilities of transcultural and lateral coexistence beyond existing national and political borders, N H D M investigates the spatiotemporal landscapes of foreign migrants in South Korea.

Seemingly peripatetic subjects, they have carved out spaces of self-determination and defined new notions of belonging with extreme specificity. N H D M provides six drawings depicting diverse past, present, and future geographies of intersecting timelines and identities in the landscapes of migrating futures, accompanied by selected responses to N H D M’s questionnaires discussing notions of home and belonging provided by individuals from migrants and immigrant communities.

Three drawings by N H D M presented together describe what constitutes the spaces of precarious domesticities lived by many transnational laborers and new immigrants.

Installation view:

The Korean Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia

Photo : Daniele Nalesso. Courtesy of the Korean Pavilion.

Domiciles Drawings

Three composite drawings, A Home is Not a Vinyl House (Domicile #1), World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2), and A Machine for Living In (Domicile #3) describe three most prevalent informal living situations currently experienced by many migrant workers in Korea, respectively describing a PVC vinyl house where seasonal agricultural workers are often housed, a Goshiwon (rentable study rooms) in urban setting usually serving as an initial housing solution for the newly arrived, and shipping container dormitories in small manufacturing sites in rural areas.

Home is not a (Vinyl) House

N H D M Architects, "Home is not a (Vinyl) House" from "Migrating Futures," 2023. Digital print on paper. © N H D M Architects, Courtesy of N H D M Architects.

World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2)

N H D M Architects, "World-Goshi-Chon (Domicile #2)" from "Migrating Futures," 2023. Digital print on paper. © N H D M Architects, Courtesy of N H D M Architects.

Home is

The first series of Migrating Futures Survey Project "Home is" engages members of diverse migrant and immigrant communities residing in Gyeonggi Province to document their evolving notions of home as well as the realities of their dwelling. Materials presented here are selected from survey answers, interviews, photographs, drawings, poems, letters, and essays, collected from more than twenty-four immigrant and migrant organizations and eighty individuals, responding to prompts to reflect on the meanings of home, belonging, and future.

Six Scenes from Migrating Futures

Inspired by the artistic traditions of various Asian origins where landscape imageries often frame the critical environment that co-constitutes one's physical and/or ideological journey, and impelled by their layered construction that is both the re-presentation of the existing and the framework for the alternative world-making, the drawings in the hexaptych formation describe six anthropocenic landscapes of migration of multivalent timelines and identities, to seek the spaces of empathy and the possibilities of new comunality.

Ansan Series—Measure Island (Ansan #1), Take the 4 Train (Ansan #2), Banwol Archipelago (Ansan #3)--- depicts the past, present, and future geographies of migrancy set around the eponymous industrial town, often referred to as "Foreigners' City" or "Migrants' Town" by Korean nationals.

Three interwoven drawings—A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House), Head of Two Waters, and Masuk Moru—explore three sites of transnational migrant work most prevalent in Korea, respectively engaging the space of domestic care labor, small-scale factory production, and agriculture.

Measure Island (Ansan #1)

(Bottom Left)

The small island at the foot of Ansan has been called Measure Island for many generations as the local fishermen noted the changes in ebb and flow against its complete and round shoreline. The construction of the seawall in 1985 that allowed Korea's very first National Industrial Complex, Banwol, to flourish however not only mined away the sacred peak of the island but gradually turned it into a part of the new ground deprived of its livelihood. The drawing imagines a not-so-distant future when most of the built-up land is underwater and the Island is surrounded by the sea again. The man-made topologies of water and land on the island bring forward the parallel past and the present of migration. An elderly fisherman who fled North Korea is forced to flee his home again. A Korean migrant worker is put to the arduous labor of the "reclamation" of a foreign land in the 1980s Middle East.

Take the 4 Train (Ansan #2)

(Top Center)

Prompted by the concentration of migrant workers in the 90s, the streets of Ansan's Wongokdong, or “Wongok Multicultural Special Zone” as the government puts it, grew to be a home away from home for many. The foreign migrant population in Korea increases steadily as the Ministry of Employment and Labor systematically recruits through the "Memorandum of Understanding" signed with sixteen countries while many are undocumented. The 4 train connecting Ansan to the center of Seoul has become a collective route of weekly rituals to visit the ethnic restaurants and places of worship, and occupy public spaces for cultural expressions and political actions. The spontaneous enclaves of diasporic hybrid culture and places of intersectional care and support have developed along the line, and in an imagined future, the train and its surrounding areas become an unbounded extraterritory where borders are eroded and all cultures are celebrated beyond the constriction of a "special zone."

Banwol Archipelago (Ansan #3)

(Bottom Right)

Ansan has been a space of coexisting yet divergent utopias, a testing ground for different idealisms. The ambitious terraforming of the Banwol Industrial Complex in 1977 was accompanied by the very first “New Town” in Korea, erected in the familiar blueprints of Howard's Garden City and Wright's prairie homes to welcome newcomers while displacing the existing population. The same footprint now holds ever-growing apartment towers that promise secure investments and pleasant living for native Koreans, while the factory jobs that Koreans avoid become a tentative basis for the “Korean dream.” In Banwol Archipelago, the City of Ansan is partially submerged creating a network of islands in the site of Banwol Industrial Complex that becomes a new aqueous collective ground for human and more than human migrating communities. The underwater factories become a refuge for a growing number of flora and fauna, and the toxicity of its industrial past becomes a foundation for a new habitat.

A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House)

(Top Left)

An ultimate instrument of personal financial safety inherited wealth and poverty, and a monument to the corporate capital accumulation aided by governmental policies, the overbuilt residential highrises cover the Korean cities and countryside, occupying much of the buildable land. A-PA-Tu complexes and their destruction and construction form cyclical and ubiquitous man-made geologies that replicate the preconceived ideas of the idealized nuclear family life. Unseen are the realities of domestic labor and care work performed more and more by foreign women in the global care chain within what some call “an international division of reproductive labor.” Intimate labor is much less shaped by intimacy than by the formidable structural forces of patriarchy, capitalism, and often racial disparity. A-Pa-Tu (Keeping House) describes the scene of vacant and "unkept" A-Pa-Tu buildings of the near future most likely from the continued market speculation, or, due to the end of the prescribed reproductive sphere. The empty towers become an opportunity for new inhabitants and new environments, or finally homes for their keepers.

Masuk Moru

(Bottom Center)

On the one hand, Masuk, a well-known furniture factory town, represents the quintessential rural industrial town in Korea, where population decline closes schools and the plans for large-scale development threaten the fabric of its small-town life. On the other hand, Masuk is a place of rare intersectional communality where the inhabitants and carers of the long-historied Leper colony embrace the migrant workers as part of their own community, offering a sanctuary from labor abuse and other difficulties of migrant life. Masuk Moru depicts a future scene of an abandoned elementary school, where the ideologies of nation-state used to be foregrounded for the next generations. Now taken care of and inhabited by transnational inhabitants, who are able to negotiate the new environments with the old, the mobility with the stability, the school becomes a space of new types of knowledge production and exchange where different notions of work and belonging shape the new starting point.

Head of Two Water

(Top Right)

Located at the scenic convergence of two water bodies (one from North Korea and one downstream from Seoul), Head of Two Water was once a much smaller river that expanded to its present size when a dam was constructed in 1972 to supply clean water to Seoul, inundating and displacing small farming communities and with great ecological implications. In the Tonle Sap area in Cambodia home to many of this region's seasonal agricultural workers, climate change threatens their livelihood in an opposite way by not inundating and depleting the nutrition in the soil, prompting more people to submit to the remittance economy. Foreshadowing an impending drop in water levels due to climate change, Head of Two Water imagines a future where the waters return again to their historic extents producing new land and a new relationship between land and who cultivate it.

Take the 4 Train

N H D M Architects, "Take the 4 Train" from "Migrating Futures," 2023. Digital print on paper. © N H D M Architects, Courtesy of N H D M Architects.