전시

-

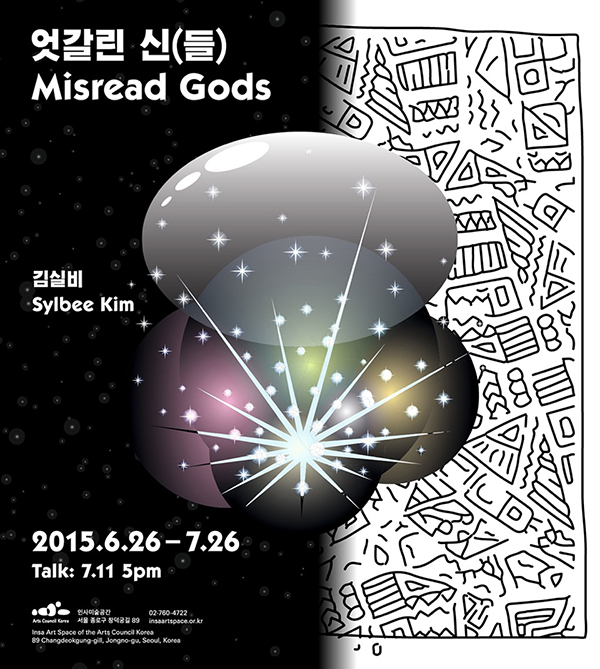

김실비 개인전_엇갈린 신(들)

김실비 개인전_엇갈린 신(들)- 전시기간

- 2015.06.26~2015.07.26

- 관람료

- 오프닝

- 장소

- 인사미술공간

- 작가

- 부대행사

- 주관

- 주최

- 문의

첨부파일

엇갈린 신(들) / Misread Gods

Artist : 김실비 / Sylbee Kim

2015. 6. 26 - 7. 26

Talk : 7.11 5pm 인사미술공간

(진행: 서울시립미술관 박가희 큐레이터 )

마테오 파스퀴넬리「고향·서식지·구멍.디지털을 통한 미술의 전치」

“아마도 예술은 동물이 시작한 것이다. 적어도 어떤 영토를 깎아내어 집을 짓는 동물이라면.” 언젠가 프랑스 철학자 두 사람은 이렇게 썼다.1 우리는 여기에 예술이 언제나 인간 영혼을 위한, 한시적이거나 허구적인 서식지를 투영한 것이라 덧붙일 수도 있으리라. 예술은 탐사된 적이 없는 광대한 영토와 친숙한 거처 사이의 공간을 가로질러 주거한다. 김실비는 익숙한 실존과 세계의 전망이 주는 안락한 좌표를 전치시키고자 한다. 영상 작업 「엇갈린 신(들)」의 한 대목에서 아즈텍의 젊은 마지막 왕, 몬테수마 2세는 이렇게 말한다.

어디에도 집을 갖지 못하는 사람들을 생각한다.

내가 얻은 적이 없는 집에 사는 일을 생각한다.

침략은 담을 넘으며 시작된다.

지구화 시대에 우리의 집은 어디인가. 우리의 고향Heimat은 어디에 있는가. 집이라는 감각은 늘 문제적이면서도 또 늘 필요한 것인데, 예술은 이를 어떻게 살아내고, 교란시키고, 약탈하는가. 김실비의 작업은 전지구적 디지털화가 정체성을 폭발시킨 세대의 전치감각을 흡수한 것으로 보인다. 새로운 종류의 정복자들이 당도하는 것을 숱하게 목격한 여러 도시와 서식지의 세계도 담긴다. 그리고 정복자는 점점 더 비가시적으로, 그러나 치명적으로 유입되는 자본의 꼴로 그 곳에 등장한다.

「엇갈린 신(들)」 (2015) 단채널 4K, HD 변환, 16:9, 색, 소리, 10분 42초

Misread Gods (2015) Single channel 4K transferred to HD, 16:9, color, sound, 10’42”

「엇갈린 신(들)」에서 이름 모를 도시의 풍경은 추상적이고 동떨어진 배경을 이룬다. 이는 마치 우리가 저가 항공을 타고 익숙하게 가로지르는 지구적 연속체와도 비슷하다. 우리는 김실비의 작업에 등장하는 도시 풍경을 알아볼 수 없다. 도시는 지구화된 인식의 스크린이기도 한, 디지털 배경이 되어 사라진다. 그러나 작가가 다년간 거주해온 베를린의 거리를 간혹 알아볼 수도 있다. 베를린이 다난한 공간 감각을 대변하는 핵심적인 대도시라는 사실 또한 우연이 아니다. 그 곳은 제2차세계대전 동안 파괴되고 두 차례 전체주의 정부에 의해 식민화되었다. 무정부주의자, 예술가, 이민자들에 의해 무단 점거되었으며, 근래에는 단체 관광지로 전락하며 상업화gentrified되었다. 마치 유럽의 실체 없는 수도처럼 건재하며, 폐허 미학의 발상지로서 베를린이라는 관념은 오늘날에도 자기 증명에 분투하는 배아 상태의 정체성이다.

베를린의 전치된 도시 정체성과 함께 서울의 현재-기억을 호흡하는 김실비의 작업은 생명의 서식지에 대한, 또 ‘거대한 외부’에 노출된 우리 욕망의 자족적 공간에 대한 성찰이다. 또한 영토, 집, 동네, 자기만의 방, 사적이고 친밀한 관계, 그리고 ‘인격적 실체’persona에 대한 우리의 인식 및 경험에 침투한 디지털 매체에 대한 성찰이기도 하다.

인사미술공간 지하 전경

Installation view of Insa Art Space basement

「제명당한 미래 RB, G」 (2015) 3채널 4K, HD 변환, 16:9, 색, 무음. 전면 및 배면 양면 영사3분 27초, 무한반복. 단채널 영사 4분 46초, 무한반복

The Expelled Future RB, G (2015) 3-channel 4K transferred to HD, 16:9, color, mute, front and rear double projection, 3’27”, loop; single projection, 4’46”, loop

독일어에서 고향, 하이마트Heimat라는 단어는 조국, 모국 또는 본국과는 전혀 다른 함의를 띤다. (역자 주: 하임Heim은 집을 뜻한다) 조상의 혈통을 바탕으로 세워진 국가 개념과는 애초에 무관하다. 고향은 언제나 주관적인 영역으로, 시간, 사회, 문화, 기술 등 보다 확장된 영역을 포함하면서 증폭될 수 있다. 독일어로 고향은 환경Umwelt에 긴밀히 연결되는데, 이 환경이란 거대한 세계Welt에 대항하여 우리가 자체적인 실존을 통해 주변에 직접 투영한 세계를 일컫는다.이에 반해 거대한 세계는 외부에 존재하며 우리를 둘러싸고 있다. 여기서 독일과 아시아의 문화 사이에 얼마간의 공통된 근원을 발견하게 된다. 양쪽 모두 공간을 인간의 시점에서 중심을 차지한 무언가로 설명하고 인식한다. 김실비의 디지털 세계는 이 편안하고 전통적인 균형을 파괴하며, 지구화와 디지털화의 시대에 인간의 공간에 침투하는 기술적·실존적 분절을 폭로한다.

김실비의 작업에서 베를린은 이국적인 깨진 거울의 비-공간으로 드러난다. 흥미롭게도 프로이트가 말한 기묘함uncanny은 독일어로 본래 ‘운하임리히’Unheimlich였는데, 익숙하지 않은 것, 집에 포함되지 않는 것을 뜻한다. 김실비의 영상과 설치 구조는 다양한 층위에서 일상성과 방향 감각에 균열을 일으킨다. 그의 영상과 스크린 설치작에서 나는 이미지의 뒤에 도사리고 있는 디지털 동굴을 본다. 그 무한한 회색조의 검정 배경이 주는 기묘함 / 낯섦 / 생소함의 효과를 느낀다. 또한 그의 설치가 구축하는 공간에서 나는 어떤 친밀함의 구멍을 감지한다. 그것은 지리적 구멍이자 사회적 구멍이다. (아마도 자전적이기도 할)그 구멍은 김실비의 고향, 서식지, 집을 품고 있다.

「왼손이 하는 일을 오른손이 모르게 하라」 (2015) 2채널 4K, HD 변환, 9:16, 색, 무음, 2분 59초, 무한반복

Don't Let Your Right Hand Know What Your Left Hand Is Doing (2015) 2-channel 4K transferred to HD, 9:16, color, mute, 2’59”, loop

이는 내밀함, ‘집-다움’Heimlichkeit의 반전이다. 그의 세계에서 우리는 더 이상 주변 공간에 지속적으로 그리고 권태롭게 자신을 투영하며 우주를 구축할 필요가 없다. 내부 세계를 외부 세계로, ‘내재감각’endosensation을 ‘외재감각’exosensation으로 교체하기를 상상해볼 수 있다. 우리는 ‘거대한 외부’로부터 우주를, 예기치 못한 우정을, 끝없는 여행을 훔쳐옴으로써 우리의 서식지를 지어볼 수 있다. 세계의 중앙에 우리는 구멍을 하나 남겨 둔다. 그러나 언제나 이 구멍을 따라 그려보는 예술가가 있게 마련이다.

「내장 속 우주 ASMR」 (2015) 음향 재생기, 스테레오 시스템, 15분 2초, 무한반복

Visceral Universe ASMR (2015) Sound player, stereo system, 15’02”, loop

“아마도 예술은 동물이 시작한 것이다.” 글머리에 언급한 구절에서 들뢰즈와 가타리는 제창하였다. 실제로 김실비의 예술 세계 어디쯤에 동물이 사는지 의아해질지도 모른다. 분명 그의 이미지는 깃털의 성격을 띤다. 찰나적인 가상의 깃털은 디지털 스크린의 무한한 공간에서 잇따라 떨어져 내리고, 계속해서 디지털 인식의 다양한 층위를 가로질러 구성된다. 호주의 우림에 사는 바우어새Scenopoeetes dentirostris는 이와 비슷하게 서식지를 준비한다. 나뭇잎을 땅에 떨어뜨린 후 하나하나 색이 옅은 쪽으로 뒤집어 놓는다. 잎사귀는 깃털의 연장이면서 동시에 그 위에서 노래하는 새의 무대가 된다. “그것은 완전한 예술가이다.” 들뢰즈와 가타리는 말한다. 그러나 예술가는 우주의 중심에 구멍을 내는 능력 때문에 동물과는 다를 것이다. 동물은 바로 그 구멍에 그저 안전한 집을 짓고 말 것이므로.

1. 질 들뢰즈·펠릭스 가타리, 『철학이란 무엇인가』, 이정임, 윤정임 옮김(현대미학사:1995).

마테오 파스퀴넬리는 베를린 기반의 이탈리아 철학자이다. 정치철학, 매체론, 인지과학에 걸쳐 다양한 학제와 미술 기관에서 집필, 강의 및 전시 기획을 하고 있다. 주요 저서로 국내 발간된 『동물혼』 (2013)이 있다.

http://matteopasquinelli.com/

Matteo Pasquinelli

“Heimat Habitat Hole: On the Digital Displacement of Art”

“Perhaps art begins with the animal, at least with the animal that carves out a territory and constructs a house,” two French philosophers once wrote.1 We may add: art is always the projection of a temporary or fictional habitat for the human soul. Art crosses and populates the space between vast unexplored territories and the familiar dwelling. Sylbee Kim displaces the reassuring coordinates of this vision of the world and of our homely existence. In her video Misread Gods, the young Moctezuma I I, the last king of the Aztecs, delivers an invocation:

Think of the people

whom no house can host.

Think of living in a house

which doesn’t belong to me.

Invasion starts

from crossing over the wall.

Where is our house in the age of globalization? Where is our homeland, our Heimat? How is art inhabiting, disrupting or looting the always-controversial and always-necessary sense of home? The work of Sylbee Kim absorbs the feeling of displacement, of a generation whose identity has been exploded by global digitization, of a world whose habitat and cities have witnessed the arrival of a new species of conquerors many times over.more and more often in the form of the invisible yet highly fatal flows of capital.

In Misread Gods the urban landscape of an unknown city plots an abstract and detached background, similar to the global continuum that we are accustomed to crossing in our lowcost airline travels. We do not recognize the urban landscape in Kim’s work. It disappears against a digital background that is simultaneously the screen of our globalized perception. Yet some will recognize the streets of the city of Berlin, where Kim has been living and working in recent years. It is by no chance that Berlin happens also to be the metropolitan nucleus of a contested sense of space: the city was destroyed in World War II, colonized by two totalitarian regimes, occupied by anarchist squatters, artists and migrants, and. most recently. gentrified vis-a-vis the lows of mass tourism. Ever enduring as the missing capital of Europe, the mother of the ruin aesthetics, Berlin manifests an embryonic identity that even today is struggling to emerge. Taking in the displaced urban identity of Berlin in the same breath as her present memories of Seoul, Kim’s work is a reflection on the habitat of life, the self-contained space of our desires that is forever exposed to the Big Outside. It is a reflection on the territory, on the house, the burrow, your private room, your intimate relations, the digital media. all of which have assimilated them selves into the perception and experience of our persona.

In the German language, the word Heimat has a completely different connotation than, for instance, fatherland, motherland or homeland; in origin, the term does not refer to the idea of a nation founded via one’s ancestors’ blood. Heimat is always a subjective sphere that can be expanded by embracing the further extended spheres of time, society, culture, technology and so on.Heimat, in German, is closely related to Umwelt, which refers to the world that we directly project around us through our own existence.against the presence of a big world (Welt) that, on the contrary, surrounds us as an external presence. It is intriguing to remark that here German and Asian culture seem to share some common roots: they both describe and perceive space as something that is always centered around the human perspective. Kim’s digital Unheworlds destroy this reassuring and traditional equilibrium and unveil the technological and existential fragmentation that is endlessly infiltrating the human space here and now in the age of globalization and digitization. Berlin, in Kim’s work, appears as an exotic non-place of broken mirrors. Interestingly, the original word for Freud’s notion of uncanny is the German Unheimlich, meaning that which is not familiar, which does not belong to the sphere of the house. Kim’s moving images, as much as the structure of their installations, disrupt domesticity and spatial orientation at divergent levels. Watching her videos and screen installation, I feel this uncanny / unfamiliar / alienating effect within the infinite grayish-black background of the digital cave that looms beneath her imagery. Within the spatial construction of Kim’s installation I also sense the construction of an intimate hole, one that is geographical as much as social. It is a hole (and most likely a biographical one, too) that inhabits Kim’s Heimat, habitat, house. It is the reversal of a sensation of familiarity, of Heimlichkeit. In Kim’s world we no longer need to construct our universe by continuously and tediously projecting ourselves in the space around us. Now we can imagine replacing our interior world with the exterior world, replacing endosensation with exosensation. We can build a habitat by stealing from the Big Outside of the universe, of unexpected friendships, of infinite travels. And at center of our world we simply leave a hole. Still, there is always an artist that is tracing this hole.

“Perhaps art begins with the animal,”hypothesized Deleuze and Guattari in the passage that opens this commentary. We could, indeed, wonder where in Kim’s artistic universe the animal is. Surely Kim’s images have the quality of feathers, of ephemeral virtual plumes that continuously fall out of place from the infinite space of the digital screen, and are unceasingly composed throughout the different layers of digital perception. In the Australian rain forests, the Bowerbird (Scenopoeetes dentirostris) prepares its habitat in a similar way: it cuts leaves from trees so that they fall on the ground and then turns each of them upside down, exposing only the sides with a lighter color. These leaves are at the same time an extension of the bird’s plumage and a natural venue to host its singing performance. “It is a complete artist,” said Deleuze and Guattari. Yet the artist is probably always different from the animal, thanks to her ability to carve a hole in the center of the universe right there, where an animal would only make a safe house.

1 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, What is Philosophy? (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), p. 183.

Matteo Pasquinelli is a Berin-based Italian philosopher. He lectures frequently at the intersection of political philosophy, media theory and cognitive sciences in universities and art institutions. His texts have been translated in many languages, among others his book Animal Spirits: A Bestiary of the Commons (2008) was published in Korean in 2013.

http://matteopasquinelli.com/

“Heimat Habitat Hole: On the Digital Displacement of Art”

“Perhaps art begins with the animal, at least with the animal that carves out a territory and constructs a house,” two French philosophers once wrote.1 We may add: art is always the projection of a temporary or fictional habitat for the human soul. Art crosses and populates the space between vast unexplored territories and the familiar dwelling. Sylbee Kim displaces the reassuring coordinates of this vision of the world and of our homely existence. In her video Misread Gods, the young Moctezuma I I, the last king of the Aztecs, delivers an invocation:

Think of the people

whom no house can host.

Think of living in a house

which doesn’t belong to me.

Invasion starts

from crossing over the wall.

Where is our house in the age of globalization? Where is our homeland, our Heimat? How is art inhabiting, disrupting or looting the always-controversial and always-necessary sense of home? The work of Sylbee Kim absorbs the feeling of displacement, of a generation whose identity has been exploded by global digitization, of a world whose habitat and cities have witnessed the arrival of a new species of conquerors many times over.more and more often in the form of the invisible yet highly fatal flows of capital.

In Misread Gods the urban landscape of an unknown city plots an abstract and detached background, similar to the global continuum that we are accustomed to crossing in our lowcost airline travels. We do not recognize the urban landscape in Kim’s work. It disappears against a digital background that is simultaneously the screen of our globalized perception. Yet some will recognize the streets of the city of Berlin, where Kim has been living and working in recent years. It is by no chance that Berlin happens also to be the metropolitan nucleus of a contested sense of space: the city was destroyed in World War II, colonized by two totalitarian regimes, occupied by anarchist squatters, artists and migrants, and. most recently. gentrified vis-a-vis the lows of mass tourism. Ever enduring as the missing capital of Europe, the mother of the ruin aesthetics, Berlin manifests an embryonic identity that even today is struggling to emerge. Taking in the displaced urban identity of Berlin in the same breath as her present memories of Seoul, Kim’s work is a reflection on the habitat of life, the self-contained space of our desires that is forever exposed to the Big Outside. It is a reflection on the territory, on the house, the burrow, your private room, your intimate relations, the digital media. all of which have assimilated them selves into the perception and experience of our persona.

In the German language, the word Heimat has a completely different connotation than, for instance, fatherland, motherland or homeland; in origin, the term does not refer to the idea of a nation founded via one’s ancestors’ blood. Heimat is always a subjective sphere that can be expanded by embracing the further extended spheres of time, society, culture, technology and so on.Heimat, in German, is closely related to Umwelt, which refers to the world that we directly project around us through our own existence.against the presence of a big world (Welt) that, on the contrary, surrounds us as an external presence. It is intriguing to remark that here German and Asian culture seem to share some common roots: they both describe and perceive space as something that is always centered around the human perspective. Kim’s digital Unheworlds destroy this reassuring and traditional equilibrium and unveil the technological and existential fragmentation that is endlessly infiltrating the human space here and now in the age of globalization and digitization. Berlin, in Kim’s work, appears as an exotic non-place of broken mirrors. Interestingly, the original word for Freud’s notion of uncanny is the German Unheimlich, meaning that which is not familiar, which does not belong to the sphere of the house. Kim’s moving images, as much as the structure of their installations, disrupt domesticity and spatial orientation at divergent levels. Watching her videos and screen installation, I feel this uncanny / unfamiliar / alienating effect within the infinite grayish-black background of the digital cave that looms beneath her imagery. Within the spatial construction of Kim’s installation I also sense the construction of an intimate hole, one that is geographical as much as social. It is a hole (and most likely a biographical one, too) that inhabits Kim’s Heimat, habitat, house. It is the reversal of a sensation of familiarity, of Heimlichkeit. In Kim’s world we no longer need to construct our universe by continuously and tediously projecting ourselves in the space around us. Now we can imagine replacing our interior world with the exterior world, replacing endosensation with exosensation. We can build a habitat by stealing from the Big Outside of the universe, of unexpected friendships, of infinite travels. And at center of our world we simply leave a hole. Still, there is always an artist that is tracing this hole.

“Perhaps art begins with the animal,”hypothesized Deleuze and Guattari in the passage that opens this commentary. We could, indeed, wonder where in Kim’s artistic universe the animal is. Surely Kim’s images have the quality of feathers, of ephemeral virtual plumes that continuously fall out of place from the infinite space of the digital screen, and are unceasingly composed throughout the different layers of digital perception. In the Australian rain forests, the Bowerbird (Scenopoeetes dentirostris) prepares its habitat in a similar way: it cuts leaves from trees so that they fall on the ground and then turns each of them upside down, exposing only the sides with a lighter color. These leaves are at the same time an extension of the bird’s plumage and a natural venue to host its singing performance. “It is a complete artist,” said Deleuze and Guattari. Yet the artist is probably always different from the animal, thanks to her ability to carve a hole in the center of the universe right there, where an animal would only make a safe house.

1 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, What is Philosophy? (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), p. 183.

Matteo Pasquinelli is a Berin-based Italian philosopher. He lectures frequently at the intersection of political philosophy, media theory and cognitive sciences in universities and art institutions. His texts have been translated in many languages, among others his book Animal Spirits: A Bestiary of the Commons (2008) was published in Korean in 2013.

http://matteopasquinelli.com/