전시

-

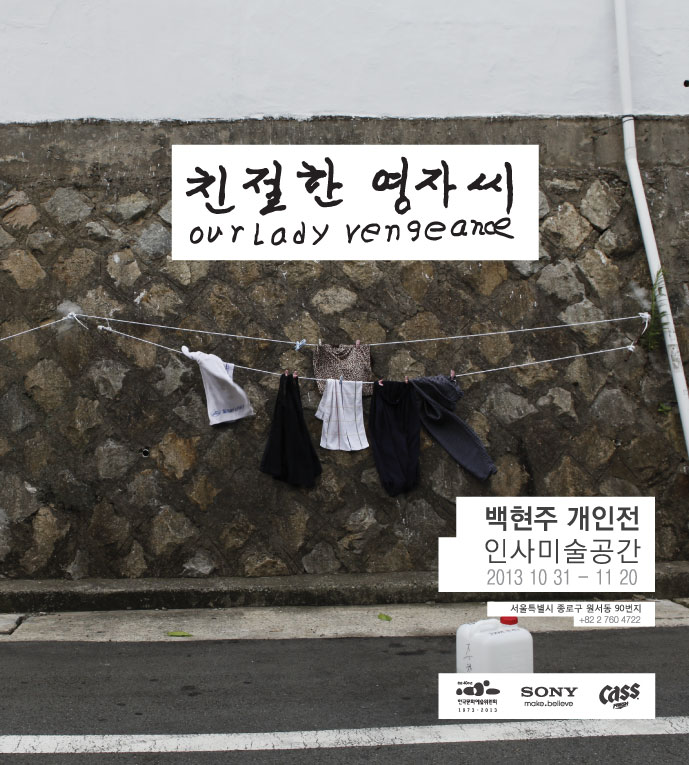

백현주 개인전_친절한 영자씨

백현주 개인전_친절한 영자씨- 전시기간

- 2013.10.31~2013.12.01

- 관람료

- 오프닝

- 장소

- 작가

- 부대행사

- 주관

- 주최

- 문의

첨부파일

.백현주 개인전_친절한 영자씨

2013.10.31 - 2013.12.01

백현주

ENGLISH

PHOTO

<친절한 영자씨> 백현주 개인전

2013.10.31(목) - 2013.12.01(수)

Q: 이단지_아르코미술관 큐레이터, A: 백현주_작가

Q: 우선 전시 제목을 본 사람들은 우리에게 익히 알려진 감독의 영화 <친절한 금자씨>를 떠올리게 마련일 것 같습니다. 이번 전시 <친절한 영자씨>의 시작과 그 과정에 대해 소개해 주실 수 있을까요?

A: <친절한 영자씨>는 말씀하신 대로 ‘친절한 금자씨’의 촬영장소인 부산 진구 개금2동 에서 제작되었습니다. 2년 전 부산에서 기획된 전시에 참여하게 되었는데, 그 기회를 빌어 주례동을 알게 되었고 그 곳 주민들과 인터뷰를 하면서 이번 작업을 기획하게 되었어요. 인터뷰에 참여한 동네 어르신들의 기억은 촬영현장을 직접 본 이후부터 계속해서 바뀌거나 소실되었고 지금은 영화 속 주인공의 이름을 ‘영자’나 ‘춘자’로 부르고 있는 집도 더러 생겼습니다. 이들 중에는 실제로 영화관에서 ‘친절한 금자씨’를 보신 분들도 있었지만 영화를 보지 않은 분들이 더 많았고, 그들의 기억은 유명한 영화의 기승전결이나 배우보다 그 영화의 촬영장소가 바로 ‘우리 동네’, ‘우리 집’ 앞이었다는 어떤 자부심 같은 것들이었습니다.

저는 그 분들이 기억하고 있는 장면을 토대로 <친절한 영자씨>라는 새로운 시나리오작업을 전개하였고 여러 계절에 걸쳐 같은 장면을 촬영하는 것으로, 기억에 의한 구술을 다시 쌓아 올리는 형식의 영상 작업을 진행했습니다.

▶ 친절한 영자씨 단채널 영상, 12’45”, 2013

Q: 동네 주민들이 가지고 있는 기억으로 다시 다른 사건(영화)을 구성한다는 것은 어떤 의미인가요?

A: 워낙 알려진 영화이기 때문에 <친절한 영자씨>를 제작 하는 것 자체가 흥미로운 출발이었습니다. ‘친절한 금자씨’라는 영화는 조용하던 마을에 어느 순간 일어난 “사건”이었을 것이고, 그 사건은 그 곳에 사는 거주민들에게 ‘우리 동네’라는 장소로써의 공통의 환기를 가져다 주었다는 점이 이번 작업의 동기가 된 것 같아요. 촬영을 위한 방문과 인터뷰를 여러 번 반복하면서 주민들의 기억은 더 이상 영화<친절한 금자씨>에 대한 것이 아니라 그들이 살고 있고 존재하는 동네, 개금2동의 현재에 대한 있는 그대로의 기억이라는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 따라서 ‘영자씨’이거나 ‘춘자씨’라는 이름 자체만큼 그들이 가지고 있는 기억의 존재 자체가 어떤 지역적인 유산, 달리 표현하자면 동네에서 일어난 사건을 ‘타자’가 아닌 스스로의 목격이나 증언으로 살아 있게 만드는 이 마을의 역사가 되지 않을까 하는 생각이 들었습니다. 사실 ‘친절한 금자씨’라는 영화의 배경으로 마을이 존재했던 것이 아니라 계속 있어왔던 마을에 영화가 들어온 것뿐이니까요. 개인과 사회, 이방인과 거주민 등 다양한 입장이 모여 이루어진 상황이나 공동체의 안팎에 대해 지속적인 관심을 가져온 저로써는 <친절한 영자씨>의 제작과정이 매끄럽지 않은 기억의 채집이라는 출발, 그리고 어수선하지만 오랜 기간 동안의 만남과 대화를 통한 기록과 복원이라는 방법을 선택한 점에서 의미를 가진다고 생각합니다. 이방인의 개입을 통해 객관성을 유지 하는 방식이 아니고, 더러는 주민을 화합시키거나 재건하는 방향이 아니라 작업, 주민들의 리얼리티를 복원함으로써 그들의 마을에 제가 참여할 수 있게 된 실험적인 작업 과정이었습니다.

▶ 고양이 진아 단채널 영상, 11’14”, 2013

Q: 작가의 노트들을 훑어보면서 “사람”이라는 단어가 유독 많이 등장하는 것이 인상적이었습니다. “노동자, 동네 주민, 항해사, 부동산업자, 정치가, 예술가” 등 각자의 입장으로써의 개인에 대한 표현이기도 하겠지만, 여러 가지 관점에서 집단이 아닌 “사람”이라는 단어는 가장 평범하지만 구체적이고 궁극적으로 매우 추상적인 표현이라는 생각이 듭니다. 동시에 집단과의 거리감에서 발생하는 자유로운 의미의 “사람”이라면 한편 이상적인 사회에 대한 의지, 믿음이 느껴지는 표현이었습니다. 이에 대한 작가의 생각은 어떤 것인가요?

A: 저는 원래 사람을 좋아합니다(웃음). 사람에 대한 긍정적인 가치관은 제 작업에 자주 나타나는 부분이기도 하구요. 물론 현실의 여러 면면에서 사람들의 관계가 항상 긍정적일 수는 없겠지요. 제가 ‘사람’을 지칭하는 의미를 구체적으로 정의한다는 것은 어렵지만, 나타나는 모든 경우의 “사람”들의 현실에 관심이 있는 것 같습니다. 실제로 <친절한 영자씨>를 촬영하는 동안에도 표면적이든, 그렇지 않든 당연히 주민들과의 긴장이 있었습니다. 하지만 그런 부딪힘과 긴장은 사람 사이에서 언제나 생길 수 있는 평범한 과정이라고 생각합니다.

인미공의 2층에 설치된 아카이브 영상들에는 그런 풍경들이 등장합니다. 동네 골목에 항상 앉아 있는 고양이라든지, 동네 이웃간의 사소한 일상, 관계망 등 이런 것들이 제가 개입하지 않은 상태에서 ‘사람의 리얼리티’인 거지요. 기록의 작업 중에는 카메라를 직접 가져가서 주민들이 본인의 방안 풍경을 스스로 촬영한 기록들도 있습니다. 이 공간과 시간과 작업을 통해 모아진 개인의 리얼리티가 결국 함께 집단의 역사가 되는 것이겠지요.

▶ everything is borrowed 네온조명, 수지채널, 간접조명, 전선, 투명 실리콘, 가변설치, 220cm x 80cm, 2013

Q: 주민들과 지속적으로 함께 했던 <친절한 영자씨>의 영상과 아카이브 기록과는 다르게 지하전시장에서 설치된는 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 촬영을 진행한 작가 스스로의 주체적인 동기나 명제처럼 읽혔습니다. ‘모든 것은 덤으로 얻어졌다’, ‘빌려오지 않은 것이 없다’라는 말에서 발생하는 행위의 객체와 주체, “모든 것”이라는 관념적 지시 등에 대해 여러 생각이 들었습니다. 간접적인 표현이지만 개인과 공동체의 사회적 사이와 관계, 작가이기 이전에 집단을 마주하는 어떤 개인으로써의 단상이나 파장으로 느껴지기도 합니다.

A: 이번 작업은 극(play_영화)과 현실(reality_동네)의 차이, 또는 개인과 집단, 지역적인 이슈와 이방인의 개입 등 상당히 많은 이슈들로 비추어질 가능성이 많기도 하고, 어떤 측면에서는 오해가 생길 수도 있겠다 싶은 생각이 들어서 저의 논지를 어떤 형식으로 전달해야 할지 고민이 되었습니다. 하지만 결론적으로 저는 사회적인 울타리 안에서의 미술의 작동이 ‘답’으로 결정지어지지 않고 현재 진행형의 어떤 질문이 되기를 원하고 있습니다.

인미공의 건물에 걸어 띄우는 애드벌룬 작업 같은 경우에도 비슷한 의미를 가지게 되기를 바라고 있습니다. 주례동의 주민들에게 ‘친절한 금자씨’라는 영화가 동네에서 일어난 어떤 한 사건이 되었듯이, 이 주변 주민들에게는 이런 일이 있었고, 오늘 원서동에서도 이러한 일이 언제나 일어나고 있음을 애드벌룬을 통해 전달하고 싶습니다. 그리고 이곳과 이 동네를 환기하기 위한 사인(sign)이 되어 어떤 궁금함을 불러 올 수 있다면 좋을 것 같습니다. 그리고 많은 사람들이 애드벌룬 밑에서 함께 하고 즐거운 시간을 보냈으면 합니다.

※ <친절한 영자씨>는 카스의 후원으로 오프닝을 진행하며 소니코리아의 협찬으로 상영 및 설치 되었습니다.

▶ 애드벌룬 애드벌룬, 가변설치, 2013

2013.10.31 - 2013.12.01

백현주

ENGLISH

PHOTO

<친절한 영자씨> 백현주 개인전

2013.10.31(목) - 2013.12.01(수)

Q: 이단지_아르코미술관 큐레이터, A: 백현주_작가

Q: 우선 전시 제목을 본 사람들은 우리에게 익히 알려진 감독의 영화 <친절한 금자씨>를 떠올리게 마련일 것 같습니다. 이번 전시 <친절한 영자씨>의 시작과 그 과정에 대해 소개해 주실 수 있을까요?

A: <친절한 영자씨>는 말씀하신 대로 ‘친절한 금자씨’의 촬영장소인 부산 진구 개금2동 에서 제작되었습니다. 2년 전 부산에서 기획된 전시에 참여하게 되었는데, 그 기회를 빌어 주례동을 알게 되었고 그 곳 주민들과 인터뷰를 하면서 이번 작업을 기획하게 되었어요. 인터뷰에 참여한 동네 어르신들의 기억은 촬영현장을 직접 본 이후부터 계속해서 바뀌거나 소실되었고 지금은 영화 속 주인공의 이름을 ‘영자’나 ‘춘자’로 부르고 있는 집도 더러 생겼습니다. 이들 중에는 실제로 영화관에서 ‘친절한 금자씨’를 보신 분들도 있었지만 영화를 보지 않은 분들이 더 많았고, 그들의 기억은 유명한 영화의 기승전결이나 배우보다 그 영화의 촬영장소가 바로 ‘우리 동네’, ‘우리 집’ 앞이었다는 어떤 자부심 같은 것들이었습니다.

저는 그 분들이 기억하고 있는 장면을 토대로 <친절한 영자씨>라는 새로운 시나리오작업을 전개하였고 여러 계절에 걸쳐 같은 장면을 촬영하는 것으로, 기억에 의한 구술을 다시 쌓아 올리는 형식의 영상 작업을 진행했습니다.

▶ 친절한 영자씨 단채널 영상, 12’45”, 2013

Q: 동네 주민들이 가지고 있는 기억으로 다시 다른 사건(영화)을 구성한다는 것은 어떤 의미인가요?

A: 워낙 알려진 영화이기 때문에 <친절한 영자씨>를 제작 하는 것 자체가 흥미로운 출발이었습니다. ‘친절한 금자씨’라는 영화는 조용하던 마을에 어느 순간 일어난 “사건”이었을 것이고, 그 사건은 그 곳에 사는 거주민들에게 ‘우리 동네’라는 장소로써의 공통의 환기를 가져다 주었다는 점이 이번 작업의 동기가 된 것 같아요. 촬영을 위한 방문과 인터뷰를 여러 번 반복하면서 주민들의 기억은 더 이상 영화<친절한 금자씨>에 대한 것이 아니라 그들이 살고 있고 존재하는 동네, 개금2동의 현재에 대한 있는 그대로의 기억이라는 것을 알게 되었습니다. 따라서 ‘영자씨’이거나 ‘춘자씨’라는 이름 자체만큼 그들이 가지고 있는 기억의 존재 자체가 어떤 지역적인 유산, 달리 표현하자면 동네에서 일어난 사건을 ‘타자’가 아닌 스스로의 목격이나 증언으로 살아 있게 만드는 이 마을의 역사가 되지 않을까 하는 생각이 들었습니다. 사실 ‘친절한 금자씨’라는 영화의 배경으로 마을이 존재했던 것이 아니라 계속 있어왔던 마을에 영화가 들어온 것뿐이니까요. 개인과 사회, 이방인과 거주민 등 다양한 입장이 모여 이루어진 상황이나 공동체의 안팎에 대해 지속적인 관심을 가져온 저로써는 <친절한 영자씨>의 제작과정이 매끄럽지 않은 기억의 채집이라는 출발, 그리고 어수선하지만 오랜 기간 동안의 만남과 대화를 통한 기록과 복원이라는 방법을 선택한 점에서 의미를 가진다고 생각합니다. 이방인의 개입을 통해 객관성을 유지 하는 방식이 아니고, 더러는 주민을 화합시키거나 재건하는 방향이 아니라 작업, 주민들의 리얼리티를 복원함으로써 그들의 마을에 제가 참여할 수 있게 된 실험적인 작업 과정이었습니다.

▶ 고양이 진아 단채널 영상, 11’14”, 2013

Q: 작가의 노트들을 훑어보면서 “사람”이라는 단어가 유독 많이 등장하는 것이 인상적이었습니다. “노동자, 동네 주민, 항해사, 부동산업자, 정치가, 예술가” 등 각자의 입장으로써의 개인에 대한 표현이기도 하겠지만, 여러 가지 관점에서 집단이 아닌 “사람”이라는 단어는 가장 평범하지만 구체적이고 궁극적으로 매우 추상적인 표현이라는 생각이 듭니다. 동시에 집단과의 거리감에서 발생하는 자유로운 의미의 “사람”이라면 한편 이상적인 사회에 대한 의지, 믿음이 느껴지는 표현이었습니다. 이에 대한 작가의 생각은 어떤 것인가요?

A: 저는 원래 사람을 좋아합니다(웃음). 사람에 대한 긍정적인 가치관은 제 작업에 자주 나타나는 부분이기도 하구요. 물론 현실의 여러 면면에서 사람들의 관계가 항상 긍정적일 수는 없겠지요. 제가 ‘사람’을 지칭하는 의미를 구체적으로 정의한다는 것은 어렵지만, 나타나는 모든 경우의 “사람”들의 현실에 관심이 있는 것 같습니다. 실제로 <친절한 영자씨>를 촬영하는 동안에도 표면적이든, 그렇지 않든 당연히 주민들과의 긴장이 있었습니다. 하지만 그런 부딪힘과 긴장은 사람 사이에서 언제나 생길 수 있는 평범한 과정이라고 생각합니다.

인미공의 2층에 설치된 아카이브 영상들에는 그런 풍경들이 등장합니다. 동네 골목에 항상 앉아 있는 고양이라든지, 동네 이웃간의 사소한 일상, 관계망 등 이런 것들이 제가 개입하지 않은 상태에서 ‘사람의 리얼리티’인 거지요. 기록의 작업 중에는 카메라를 직접 가져가서 주민들이 본인의 방안 풍경을 스스로 촬영한 기록들도 있습니다. 이 공간과 시간과 작업을 통해 모아진 개인의 리얼리티가 결국 함께 집단의 역사가 되는 것이겠지요.

▶ everything is borrowed 네온조명, 수지채널, 간접조명, 전선, 투명 실리콘, 가변설치, 220cm x 80cm, 2013

Q: 주민들과 지속적으로 함께 했던 <친절한 영자씨>의 영상과 아카이브 기록과는 다르게 지하전시장에서 설치된

A: 이번 작업은 극(play_영화)과 현실(reality_동네)의 차이, 또는 개인과 집단, 지역적인 이슈와 이방인의 개입 등 상당히 많은 이슈들로 비추어질 가능성이 많기도 하고, 어떤 측면에서는 오해가 생길 수도 있겠다 싶은 생각이 들어서 저의 논지를 어떤 형식으로 전달해야 할지 고민이 되었습니다. 하지만 결론적으로 저는 사회적인 울타리 안에서의 미술의 작동이 ‘답’으로 결정지어지지 않고 현재 진행형의 어떤 질문이 되기를 원하고 있습니다.

인미공의 건물에 걸어 띄우는 애드벌룬 작업 같은 경우에도 비슷한 의미를 가지게 되기를 바라고 있습니다. 주례동의 주민들에게 ‘친절한 금자씨’라는 영화가 동네에서 일어난 어떤 한 사건이 되었듯이, 이 주변 주민들에게는 이런 일이 있었고, 오늘 원서동에서도 이러한 일이 언제나 일어나고 있음을 애드벌룬을 통해 전달하고 싶습니다. 그리고 이곳과 이 동네를 환기하기 위한 사인(sign)이 되어 어떤 궁금함을 불러 올 수 있다면 좋을 것 같습니다. 그리고 많은 사람들이 애드벌룬 밑에서 함께 하고 즐거운 시간을 보냈으면 합니다.

※ <친절한 영자씨>는 카스의 후원으로 오프닝을 진행하며 소니코리아의 협찬으로 상영 및 설치 되었습니다.

▶ 애드벌룬 애드벌룬, 가변설치, 2013

ENGLISH

Our lady vengeance

Heaven Baek solo exhibition

October 31-December 1 , 2013

What is a community? The term ‘community,’ which is spreading like an epidemic around us, seems to be at the center of the way of living pursued in the present Korean society. According to Derrida, what you see, what you feel, or what is visualized as the surface of society may not be the visualization of meaning itself, but rather a sign or the/an encoded representation of the absolute value of meaning and the passion for it. This heated enthusiasm for community is associated with Derrida’s concept of the ‘supplement,’ which is by definition related to ‘lack’ and ‘disguise.’ It may raise the question: Contrary to the common belief, isn’t it rather the lack of community that made us so heavily inclined to the discourse of it? For Derrida, the supplement means the ‘representation’ of the ‘original,’ which has a system different from that of introduction of the original. He understands representation as a way of showing mythological or absolute meanings, and the signifier, although filled with meanings, needs supplements because it is actually empty. He argues that supplements create and represent images. Then, to follow this line of argument, is public art, or community-based art the manifestation of the will to temporarily represent a fictitious community by reconstructing the absent community? Or is it a disguise to conceal the lack? Is it to highlight the state of absence with decoration? The response to the enthusiasm for and the lack of community may bring forth totally different results in accordance with the artist’s attitude. Heaven Baek’s Our Lady Vengeance, asks about the fictitiousness of community through the form of cinema or quasi-cinema, produced by the artist who herself went inside a nameless village—or more precisely, made by the artist and the residents together, or solely by the residents, or even, starring the residents. At first glance, the work may seem to take the format of Maeul Film or Village Film that is now popular in Korea, but is closer to an attempt to destroy the meaning of community that has been hitherto exaggerated and politically abused.

The Two Faces of Community

Community is a concept that cannot be explained easily. Today, it is realized as an extremist form of pursuing its own interest. For example, the labor-government conflict in the recent Korean rail workers’ strike clearly showed that every community, whether big or small, exists in multi-layered relationships. Richard Sennet argues that modern working conditions have constantly undermined ways of cooperating with other people: “In principle, every modern organization is in favour of cooperation; in practice, the structure of modern organizations inhibits it.” He explains that the reason why there are increasing needs for other forms of community or alternative ways of living different from those of the past, such as cooperation, solidarity, and union is that modern man has lost or degraded the skills of cooperation. This may leads to the more fundamental philosophical question. The conditions, meanings, and political demands relating to community are not irrelevant to the human pursuit of freedom. Noam Chomsky expands the issue of human free will even to anarchism: “For the anarchist, freedom is not an abstract philosophical concept, but the vital concrete possibility for every human being to bring to full development all the powers, capacities, and talents with which nature has endowed him.” Chomsky’s understanding of anarchism may seem to be a negation of community, but it should be understood more as the will to pursue a trans-regional or -national community with more active engagement in society, mutual respect, and kind consideration.

The earlier project of the artist, who looks like a bashful activist, would have been a process of experiencing the peculiarity of one of the communities in the region in which she intervened. In 2011, Baek embarked a five-month long project in Naechon-ri, Hongcheon-gun, Gangwon-do, Korea, which sarcastically described a housewives’ gathering as a pseudo-political party. In this Housewives Party (2011), private meetings and public issues are jumbled together. A similar kind of gathering recently appeared in a South Korean SBS TV documentary entitled The Last Power. It reported the old women’s rebellion in Gamgok village, Gyeongsangnam-do, Korea, where only men have been so far elected to be a village headman. Old female members of the village, who became increasingly displeased with the fact that village affairs were discussed and dealt with in a male-centered way, independently elected a young village headwoman and began to put themselves forward. They went so far as to meet the county headman to demand solutions. Without the help of the big symbol of politics, we know all too well about the merits and faults of power. Everyone agrees that a community belongs to its members who are actually living there, whether or not they have a confused and non-eloquent way of talking. Housewives Party shows that politics arises from the demands of everyday life. And the questions posed in the work, such as democracy, politics, everyday life, and a community of others, are expanded to her first solo exhibition at Insa Art Space, titled “Our Lady Vengeance.”

Anti-Cinema or Post-Cinema: A Question about the Reality

This project began with the memory that the residents in Gaegem 2-dong, Jingu, Busan, where Lady Vengeance had been shot, had of this Korean film. Human memory is subject to flaws and errors: they remembered even the title wrongly, and the impression left on their minds was not the narrative of revenge and violence presented in the film, but only the fact that a very famous movie, starring a very famous actress, had been shot in their village. The artist gathers these fragmented recollections with the participation of the villagers. Each talks about his or her own memory, in which sometimes, Geumja, the name of the main character in the film, is mingled with Janggeum, another main character played by the same actress in one of the most popular Korean TV series. Baek finds herself more interested, not in the influence of the fictitiousness of cinema upon the identity of the village in reality, but in the process in which the subjects of the village assimilate the film, not as the other of the large-scale capitalist industry of filmmaking, but as a positive audience or witness. It is at this point where as the artist commented, the question of what kind of relationship the cinema as fiction can have with real life has meaning.

For Jean-Luc Godard, movies are both telescope and microscope. He even adds that his life is a movie and he is himself a movie. The reason why he has to make a film is that to be himself, he needs to project myself outside. And one of the chief reasons why Baek produced Our Lady Vengeance, a deconstructive reinterpretation of Sympathy for Lady Vengeance, is to explore how cinema can be related with reality. Derrida’s concept of deconstruction means to read the original work again in a new way. This should be understood as an approach different from representation. A deconstructive approach is to draw out new interpretations within the limits or boundary of the original text. A deconstructed text is different from an appropriation of the original, although having traces of it. What constitutes the identity of Gaegeum-dong, the background of the original movie as fiction makes the audience form an idea of the mythical structure of modern society. The subversive phenomenon that fiction controls reality seems to represent the poor life in reality in a roundabout way. The change of Geumja to Yeongja highlights that Baek’s Our Lady Vengeance has nothing to do with the theme of the original work, that is, the human feeling of revenge. And the text of Geumja who was deconstructed into Yeongja appears to reinforce the fictitiousness of community, rather than to represent the illusion of it.

Our Lady Vengeance can be regarded as an anti- or post-cinema of the original. The process in which Geumja changed to Yeongja may not be solely due to a mere distortion of memory. This is because the memory of the residents who watched the shooting process is influenced by the conflicts between the filming staff and them, various collisions occurring during the filming period, and fortuitous accidents that would happen in the process to manipulate or control the reality to create a fictional world, and so on. Therefore, as the artist observed, the fact that the heroine’s name was changed from Geumja to Yeongja may summon another ‘reality.’ A ‘deterritorized cinema’ that escaped from the territory of cinema reaches the state of being away from the representation of cinema. While Sympathy for Lady Vengeance as a given event became the product of cultural industry like a readymade, Our Lady Vengeance, another movie completed with the various thoughts and views of those remembering the original film, turns into a reality represented by the so-called collective intelligence. Therefore, Our Lady Vengeance, screened on the first floor of Insa Art Space, as well as a video and a theatrical installation using objects on the second floor, could be regarded as a device to show the everyday life of the villagers and the paradoxical meaning of perspective, which are away from the inviolable representation of cinema. In addition, on the basement, the artist presents an independent space that is distinguished from the logical frame of the dialectic relationship between the original cinema and anti-cinema, and between the first and the second floor. The place, which has no bearing on this project, is dedicated to the relationship with Wonseo-dong where the exhibition is held. Baek also has a plan to create an event to float an advertising balloon during the exhibition period, which is to evoke reaction from the community with a deviant event that is out of the context of the village, as in Sympathy for Lady Vengeance. Exactly as the artist intended, the post-cinema of Our Lady Vengeance seems to succeed in presenting a new insight on reality. And even the excessive kindness to show the process of filmmaking, which may seem to put some limitations on the imagination of those who visit the exhibition, seems to serve as a strategic preparation to lay weight on the fictitious view of the world that controls reality now.

Jung Hyun